Join authors Dennis McCuistion and Dory Wiley for an explosive panel discussion at The Dallas Express’ “Who Killed JFK?” event on June 9, 2025. Get General Tickets, VIP Access, or Become a Sponsor today!

The CIA feared that Cuba’s true revolutionary export wasn’t fighters—it was a playbook for turning a country’s own resources against itself.

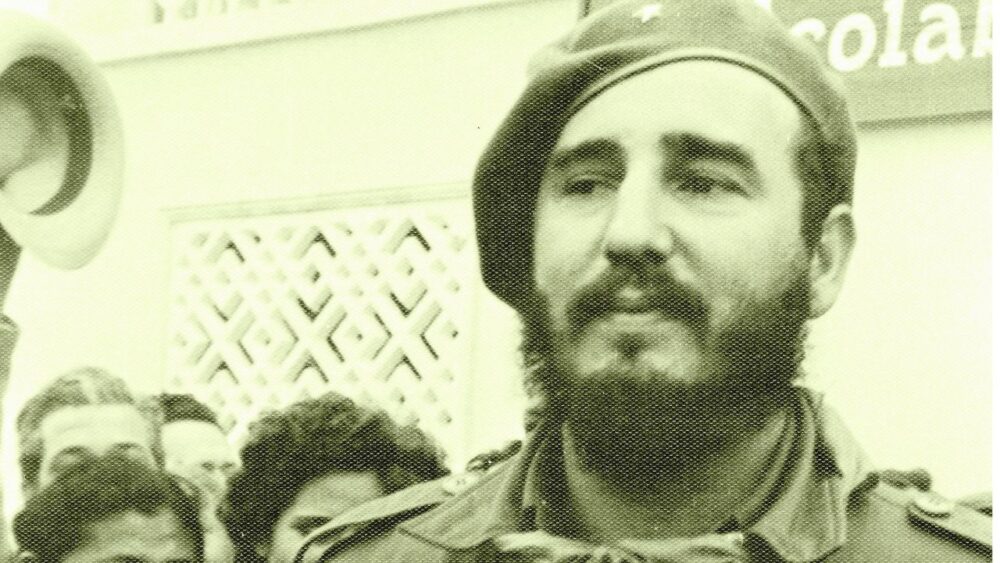

Newly declassified intelligence files from the 1960s, released by President Donald Trump in March 2025 as part of the broader “JFK Files” disclosure, detail extensive efforts by Fidel Castro’s Cuba to spread communism across Latin America—not through mass invasions or military might, but by subverting nations from within.

One such document from then-CIA Director John A. McCone to then-Senator John Stennis (D-MS) is marked “Secret” and appears to be from the spring of 1963. The document outlines the CIA’s assessment of Cuba’s subversive strategy as a potent mix of ideological indoctrination, sabotage training, and psychological warfare.

According to the report, Cuba offered revolutionaries from across Latin America a chillingly precise deal: “Come to Cuba; we will pay your way, we will train you…in guerrilla warfare, in sabotage and in terrorism.” Though the Cubans generally avoided supplying weapons or personnel, they promised political support, training materials, demolition guides, secret communication techniques, and, in some cases, funding.

The strategy focused on training guerrillas to be self-sufficient and to weaponize their surroundings.

Pocket-sized manuals, such as “150 Questions on Guerrilla Warfare” by Spanish Civil War veteran Alberto Bayo, circulated widely. They instructed revolutionaries on how to craft explosives from household items and steal arms from government forces. CIA agents found versions of these texts adapted for countries like Peru, Colombia, and Brazil.

In the early 1960s, the CIA leadership believed between 1,000 and 1,500 individuals from almost every Latin American country (except Uruguay) reportedly traveled to Cuba for ideological or guerrilla training.

The Cuban government tried to obscure the movement, issuing visas on separate slips to avoid passport stamps and even providing falsified passports. American intelligence used agents within communist parties and foreign customs authorities to track and estimate the scale of this traffic, the director told the senator.

The report highlights Cuba’s two-pronged media campaign into the United States as an early extension of this subversive agenda.

“Radio Free Dixie,” hosted by North Carolina-born Robert F. Williams, was broadcast in English to Black Americans in the South, while “The Friendly Voice of Cuba” reached a wider Southern audience. These programs, the CIA noted, could be heard clearly in Florida and across much of the Deep South and represented a subtle yet strategic psychological campaign aimed at undermining American unity.

Castro’s ambition, the report asserts, was to make Cuba the blueprint for the Latin American revolution. He famously stated in 1960 that he aimed to “convert the Cordillera of the Andes into the Sierra Maestra of the American continent.”

The Sierra Maestra was the mountain refuge from which Castro launched his successful revolution against Batista. “Socialism,” he argued, could not afford to wait for democratic change—it had to be won by force.

And yet, Cuban communism was not as militant as it might seem.

The CIA noted that Castro often trod a careful line between the Soviet Union and Communist China. “Castro’s heart is in Peiping but his stomach is in Moscow,” one section reads, referencing the ideological tug-of-war between Chinese revolutionary zeal and Soviet pragmatism.

While China promoted all-out militancy, the Soviets favored subversion through legal means. Castro attempted to serve both masters—adopting Chinese revolutionary theory but relying on Soviet material aid.

Despite this ideological balancing act, the CIA classified the Cubans and Venezuelans as the only Communist parties in Latin America “totally committed to terror and revolution.” Other parties, while ideologically aligned, preferred subversion, propaganda, and infiltration to outright violence—at least initially.

Several revolutions swept through South America during the decades following Cuba’s turn to communism, some succeeding and others collapsing. In Nicaragua, the Sandinistas ultimately overthrew the Somoza regime in 1979 with tactics reminiscent of the Cuban model. In Chile, Salvador Allende’s Marxist government came to power democratically in 1970 but was overthrown in a military coup three years later. Guerrilla movements plagued Colombia, Peru, Argentina, and Bolivia, with groups like the FARC and the Shining Path drawing from the ideological and tactical lineage traced back to Cuba’s training camps and printed materials.

Even where communist revolutions never took root—such as in Brazil, Ecuador, or Paraguay—leftist guerrilla groups launched campaigns of sabotage and terror, often mimicking Cuban tactics. Many of these movements were ultimately suppressed, but not before spreading fear and destabilization.

Perhaps the most telling metric of Cuba’s nonviolent infiltration was its printed word.

“It may be worth noting,” the CIA director wrote, “that the postal and customs authorities in Panama are destroying on average 12 tons a month of Cuban propaganda.” Another 10 tons were reportedly confiscated monthly in Costa Rica. These materials, in the form of books, pamphlets, and ideological tracts, were seen as weapons of war.

Despite accepting Soviet missiles and troops during the Cuban Missile Crisis—20,000 Soviet personnel were reportedly stationed in Cuba, according to one document—the island’s long-term strategy was quieter and more insidious. The CIA concluded that Cuba’s effort to spread communism through nonviolent means was far more effective than the Cuban effort to spread communism through violent means.