Kanye West, now known as “Ye,” sparked controversy with his latest song, “Heil Hitler.” However, his fascination with the former leader of the Third Reich has a troubling precedent.

As previously reported by The Dallas Express, Spotify and SoundCloud recently removed West’s newest track, “Heil Hitler,” from their streaming and social media platforms. The song, part of the rapper’s latest album Cuck, features lyrics like “Ni**a, Heil Hitler” and ends with a translated recording of a speech by Adolf Hitler.

The backlash has been swift. The leadership of Jewish organizations condemned Ye for releasing the song.

As Ye faces new waves of opposition, his artistic obsession with controversial figures finds precedent in the work of another once-radical musician: David Bowie.

Long before Ye’s “Villain Arc” songs, David Bowie flirted openly with fascist imagery and ideology in the mid-1970s. During that time, he made public statements expressing admiration for authoritarian leadership.

In a 1976 interview with Playboy, Bowie said, “I believe very strongly in fascism … People have always responded with greater efficiency under a regimental leadership.” He added, “Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars.”

That same year, in an interview for Rolling Stone, Bowie said he “could have been Hitler in England, and declared he’d be “an excellent dictator — very eccentric and quite mad.”

Contemporaneously, Bowie was also detained by customs officers while traveling through the Soviet Union with books on Nazi officials Joseph Goebbels and Albert Speer, which he later described as research for a film project, Uncut reported.

Photographer Andrew Kent, who was traveling with Bowie at the time, downplayed the implications in an interview several decades later: “David was just looking for something to do; it was not a political statement.”

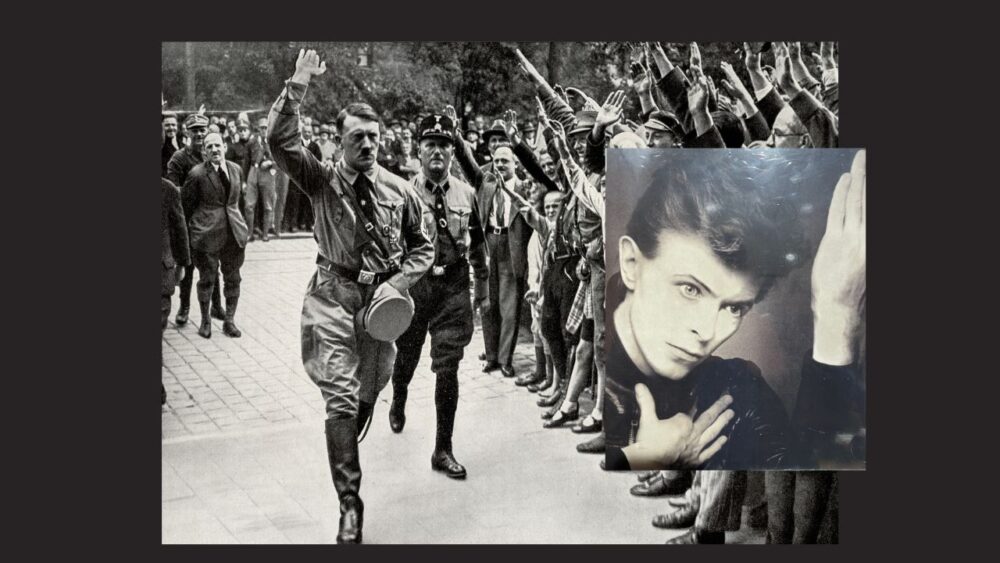

Still, rumors swirled. Occasionally, Bowie would brush up against famous images of Hitler. One instance was at London’s Victoria Station in May 1976. Photographs showed Bowie greeting fans with his arm raised stiffly from an open-top Mercedes. Hitler famously traveled to parades and public appearances while standing in the back of an open-top Mercedes.

Similar to Elon Musk’s gesture at an event around President Donald Trump’s inauguration in January, Bowie fans have long argued about whether this is an innocent wave or a salute.

David Bowie’s flirtation with fascism was perhaps a phase — one that co-occurred with an intense period of cocaine use that reportedly induced a “cocaine psychosis” in the Englishman. But the symbolism and the tension it provoked lingers in the history of Western art, which has long been fascinated by fallen powers — even that of our enemies.

From the ruins of Nazi Germany to the legacy of the Confederacy, Western artists have often drawn inspiration from civilizations that collapsed in defiance of the United States. Gone with the Wind, arguably one of the greatest American novels, romanticized the pre-war South, while countless Westerns depicted figures like Geronimo and Sitting Bull — Indians who led fierce battles against the U.S. — with awe, if not reverence.

These portrayals are not endorsements; they highlight the significant impact of lost civilizations on American and British art.

Ancient Rome and Greece inspired neoclassical architecture and Renaissance art; the Confederacy, though defeated, has influenced literature and film. Even Nazi aesthetics, as condemned as they are, have shaped iconography and storytelling — from comic book villains to fashion runways.

Bowie’s personas — from the alien messiah Ziggy Stardust to the icy Thin White Duke — often embodied this tension between the sublime and the sinister.

Ziggy fell to Earth as a savior figure but was consumed by fame. The Duke, meanwhile, was all control and elegance—with nothing beneath. These alter-egos allowed Bowie to channel ideas into human form.

Ye, by contrast, has blurred the line between performance and belief more recklessly. His lyric, “So I became a Nazi, yeah, bitch I’m the villain,” has raised questions about the degree to which this is a new ideology for the artist or performance art.

As Aaron Terr of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression previously told The Dallas Express, “Drawing lines is especially difficult when it comes to music and other art forms, which often thrive on provocation or grapple with dark subject matter.”