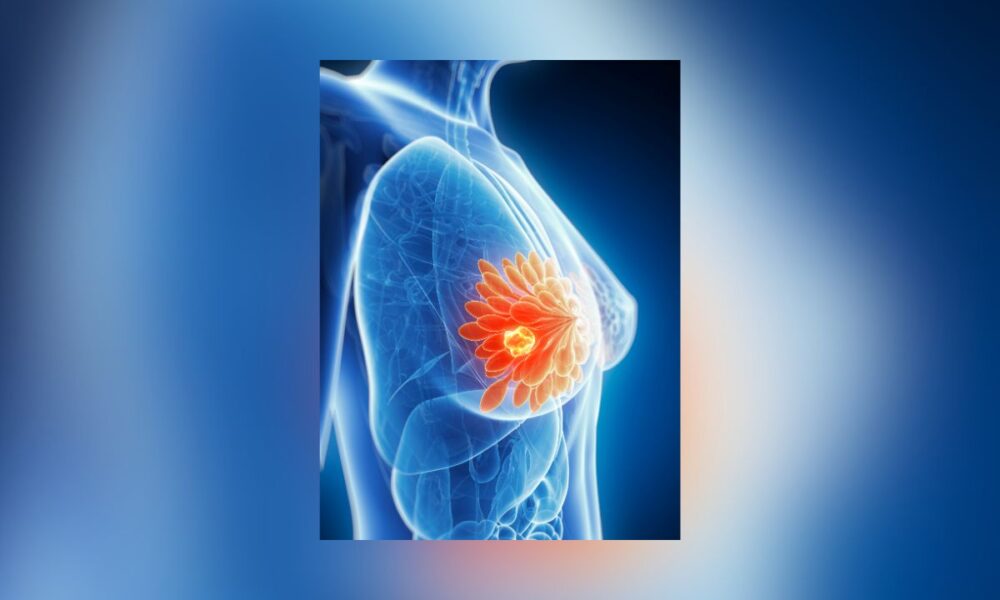

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) have uncovered a mechanism by which triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) tumors fuel growth by drawing energy from nearby fat cells. The study, published Wednesday in Nature Communications, points to potential new treatment options.

TNBC accounts for about 15% of breast cancer cases and is more common in black women and those under 40, is known for its aggressive nature and limited treatment options.

The study, lled by Dr. Andrei Goga, professor of cell and tissue biology at UCSF, found that TNBC tumor cells form molecular tunnels called “gap junctions.” These tunnels allow tumors to tap lipids in nearby fat cells, releasing stored energy to fuel cancer growth.

“Cancers thrive by hijacking the body’s energy sources, and we’ve identified how this works in triple-negative breast cancer,” Goga said in a UCSF release.

The research, funded by the Department of Defense and the National Institutes of Health, showed that blocking the gap junctions stopped tumor growth in lab models.

Using TNBC tumors from patients and mouse models, researchers found fat cells closer to tumors had less lipid content and were smaller than those farther away or in non-cancerous breast tissue. They also saw increased gene expression linked to lipolysis — the breakdown of fats — in tumors and surrounding tissue.

“Aggressive cancer cells can co-opt different nutrient sources to help them grow, including by stimulating fat cells in the breast to release their lipids,” said Jeremy Williams, a UCSF postdoctoral scholar, per NBC 5 DFW. “In the future, treatments might starve tumor cells by blocking their access to these lipids.”

The team confirmed TNBC cells form gap junctions with fat cells, transferring a signaling molecule called cAMP that promotes lipolysis. By depleting a key gap junction protein, researchers reduced this transfer and saw decreased tumor growth in mice. Tumors with intact gap junctions promoted lipolysis in surrounding fat tissue, while those without the protein showed reduced activity.

“Knocking out a single gene impaired the formation and progression of the tumor,” Williams said.

The findings align with prior research linking higher body mass index (BMI) to increased TNBC risk, suggesting fat tissue plays a role in tumor growth.

Dr. Julia McGuinness, a breast cancer specialist at Columbia University, called the study the first evidence of a mechanism linking fat to cancer growth. “It’s also suggesting one pathway to treat aggressive cancers for which we don’t have any good therapies,” she told NBC 5.

She added, “Slimming down could be protective,” noting obesity is a known breast cancer risk factor.

Justin Balko, a cancer researcher at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, said, “They found a new way cancer grows and feeds itself,” though he cautioned, “For example, we don’t know if this is a major mechanism by which breast cancer grows in humans,” NBC 5 reported.

Still, he noted, “If some of the same effects are observed in humans, it might be fodder for differences in the way we treat patients.”

The study’s implications extend beyond breast cancer, as gap junctions are also being studied in brain cancer trials, offering a potential shared therapeutic target.

“This is a golden opportunity for us to develop effective strategies to treat the most aggressive forms of breast cancer,” Goga said.