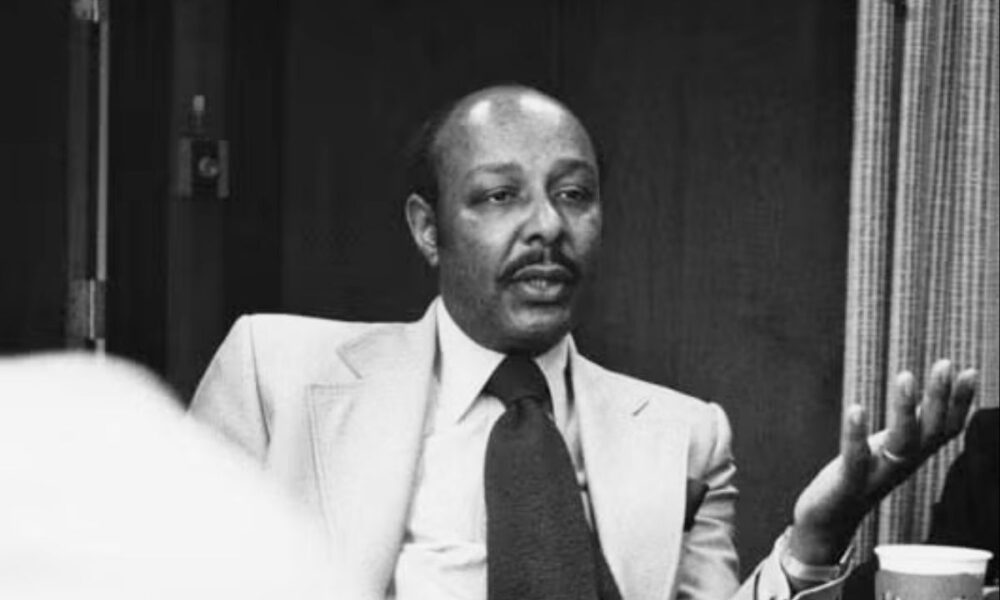

A newly revealed letter shows a powerful House congressman had warned the CIA not to release any records related to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, even under public records laws, without congressional permission.

The 1979 letter from Rep. Louis Stokes to CIA Director Stansfield Turner was declassified this week following the federal release of 230,000 pages of files tied to King’s 1968 murder.

The trove, made public on July 21 by the National Archives under Executive Order 14176, has reignited longstanding questions about the federal government’s role and awareness in the events surrounding the assassination.

Stokes, a Democrat from Ohio and former chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, chaired the House Select Committee on Assassinations’ investigation.

In the 1979 letter, Stokes urged the CIA to keep all related materials confidential unless explicitly authorized by the House.

“It can be anticipated that your Agency will receive requests under the Freedom of Information Act for access to these materials. The purpose of this letter is to request specifically that this Congressional material and related information in a form connected to the Committee not be disclosed outside your Agency without the written concurrence of the House of Representatives.”

Stokes did not provide a justification for this request.

However, the warning accompanied concerns within the CIA itself. A 1976 internal memo from Lyle L. Miller, deputy legislative counsel for the Agency, proposed a cooperative approach with Congress to gain lawmakers’ trust — but also to preserve the CIA’s own institutional interests.

“In looking to the road ahead, which may well eventually prove bumpy… it is absolutely imperative that we fortify ourselves with the Committee.”

The strategy included offering inventories of files, copies of unclassified collections, and background briefings. In exchange, the CIA hoped for “quid pro quos on security and other matters in which we have strong equities.”

House Resolution 222, passed on February 2, 1977, established the Select Committee on Assassinations with the mandate to investigate the killings of King and Kennedy. The committee’s final report, issued in 1979, concluded that both men were likely assassinated as part of conspiracies, though it failed to identify all participants.

The broader context includes longstanding skepticism about the FBI and CIA’s role in surveilling and harassing King. Public trust in official narratives eroded further after a 1999 Memphis civil jury found that James Earl Ray, who pled guilty to killing King, was part of a conspiracy that included government agencies.

“The evidence introduced in King v. Jowers to support various conspiracy allegations consisted of either inaccurate and incomplete information or unsubstantiated conjecture, supplied most often by sources, many unnamed, who did not testify,” a Department of Justice press release responded after the verdict.

King was gunned down on April 4, 1968, at a motel in Memphis, Tennessee. James Earl Ray later pleaded guilty to the killing but recanted shortly thereafter and claimed innocence until he died in 1998.

Stokes went on to become the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee. Stokes served in Congress from January 3, 1969, until January 3, 1999.

The Dallas Express is currently analyzing the 230,000 pages and will continue to report on new developments as they emerge.