This article is the first in a series by The Dallas Express that focuses on the Texas water crisis and the various proposed solutions to address the crisis.

Despite the recent and tragic flooding in the Texas Hill Country, the real story isn’t too much water — it’s not enough of it where Texans actually need it.

Texas is in the middle of an increasingly critical water crisis: A perfect storm of explosive population growth, aging infrastructure, and rising demand from residents, agriculture, and industry is draining the state’s most precious natural resource — one arguably more critical than oil or gas.

If you think this is a problem for the next generation, think again.

The Texas Water Development Board, in its 2022 plan, warned that parts of the state could be facing a major water shortfall by 2030.

So the question is — What, if anything, is being done about it? Build more reservoirs? Pray for rain? Punt to the next legislative session?

Kyle Bass and his team at his new company, Conservation Energy Management (CEM), believe part of the answer is found in allowing the private sector to solve a problem the government hasn’t yet solved – and without any cost to Texas taxpayers.

Photo: Kyle Bass and Dr. Phil at a recent Texas Department of Public Safety Fundraiser hosted at Bass’ Bluebonnet Ranch

One Answer Is Right Under Our Boots… Literally.

Bass, a Dallas-based investor, best known for his blockbuster bet against the subprime mortgage market and role advising the Trump administration on national security matters, has a new play — and it’s not on Wall Street.

It’s in Anderson, Henderson, and Houston Counties in East Texas. In Henderson County lies the 4,000-acre Bluebonnet Ranch, and in Anderson and Houston counties lies the 7,200-acre Redtown Ranch.

Bass believes the key to the Lone Star State’s water future lies beneath Texans’ boots. Specifically, in the monstrous Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer, a vast, clean groundwater reservoir that spans 23 million acres across 66 Texas counties.

According to the Texas Water Development Board, approximately 55% of Texas water comes from groundwater – the water “under your feet” that Bass refers to is groundwater stored in underground aquifers. Surface water — found in lakes, rivers, streams, and reservoirs — makes up another 42% of Texas’ water supply.

Photo: Bluebonnet Ranch

The problem, as Bass’ attorney Ed McCarthy explains, is that the vast majority of Texas groundwater isn’t where it’s needed. East Texas, where Bluebonnet and Redtown are located, is rich in groundwater, which is incredibly scarce in much drier West Texas. Bass’ plan (once it is permitted) is to pump the water from his own resource-rich properties and transport it to areas in need – for a profit, of course.

He’s drilled test holes, hired experts, and gathered scientific data. Bass says his team could draw just a sliver of water from the aquifer – enough to make a difference for many communities in need— without breaking a single law or threatening the local water supply in any way. So far, Bass has only applied to drill exploratory test wells to prove up and further support his existing science; production is not even on the table yet.

But some state and local officials in the counties where Bass and his company own these properties have sounded the alarm on CEM’s plan, which raises a bigger question: Who actually owns the water in Texas?

To understand what’s at stake, an understanding of Texas private property and groundwater law is necessary.

In Texas, surface water — rivers, lakes, and reservoirs — belongs to the state. You need a permit from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) to use it for anything beyond livestock or domestic purposes.

But groundwater is different.

Groundwater is a private property right. Thanks to a 121-year-old Texas Supreme Court-authored legal doctrine called the “Rule of Capture,” landowners can pump as much water from beneath their property as they want. No permit required. No limits. As long as the withdrawal isn’t maliciously aimed at a neighbor or wasteful, it’s perfectly legal.

This is why the “Rule of Capture” is often referred to as “the law of the biggest pump.”

But like all things in Texas, it’s never that simple.

Too Many Cooks in the Water Kitchen?

Water in Texas isn’t just a natural resource — it can be a regulatory labyrinth despite the “Rule of Capture.”

At the top, you’ve got the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), which handles water planning and development. Then there’s the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), which regulates environmental quality and public water systems.

Add in the Public Utility Commission of Texas (PUCT), which oversees water utilities in deregulated areas, and the Texas Water Foundation, which serves more of an educational and advocacy role, and you start to see the problem.

Nobody’s steering the ship.

No one is accountable for working together to get things moving. That’s how the state ends up with conflicting rules, missing data, and endless delays — while the demand for water keeps climbing.

Layers of Bureaucracy and Conflicting Authority

In addition to state agencies, we have Groundwater Conservation Districts (GCDs) — local boards charged with regulating groundwater pumping. Many are underfunded and staffed with part-time members who lack expertise in groundwater. Some counties don’t even have GCDs.

These various agencies use measurements like:

- MAG (Modeled Available Groundwater): the maximum annual amount of water that can be pumped sustainably

- DFC (Desired Future Conditions): long-term aquifer health goals

Not every county has MAG data. Anderson County didn’t — until Bass stepped in.

The Politics of Groundwater – Legitimate Concerns or Political Theater?

At a recent Texas House Committee on Natural Resources hearing called by Rep. Cody Harris, who represents Anderson County and chairs the committee, Bass testified following 8 hours of mostly hostile testimony from various elected officials, water experts (including some questionable “experts” like a one-man water well drilling business owner), and various other stakeholders.

The House Natural Resources Committee has no actual regulatory authority over Bass’ plan, which has led Bass and some observers to question the real purpose of the hearing. Harris has led the opposition to Bass’ plan. He’s conducted media interviews, posted his opposition on social media, and even hosted a local town hall meeting to educate his constituents and rally resident opposition.

Harris has otherwise historically been a staunch private property rights advocate, but was recently censured by both the Henderson and Navarro County GOPs in his own district for not supporting the House Republican Caucus vote for David Cook for Speaker, voting to impeach Attorney General Ken Paxton, and 15 other allegations. Harris challenged the censure votes and strongly refuted the counts of the respective county parties, calling them, factually incorrect” and “incongruent with Republican principles.”

Photo: Texas State Representative Cody Harris

The hearing started contentiously with Harris trying to discredit Bass before Bass testified by suggesting he had been drilling wells without a permit. Other committee members echoed that claim throughout the hearing. When Bass and his attorney, Ed McCarthy, took their turn to testify following 8 hours of what appeared to be organized opposition, they quickly dispelled the claim.

Once called to testify, Bass and his attorney adamantly dismissed the allegation that he was drilling wells without a permit, then explained that his team is providing aquifer data that the county didn’t even have.

Sen. Bob Nichols, who attended the hearing, acknowledged the credibility of Bass’s legal counsel, calling him “a legend” in Texas environmental and water law.

Bass reinforced in his testimony that he plans to operate well within MAG limits. His attorney testified that they would draw no more than 0.02% of the aquifer, which they characterized as a statistical blip. Bass offered to share the MAG data from his drill test sites with the appropriate GCDs.

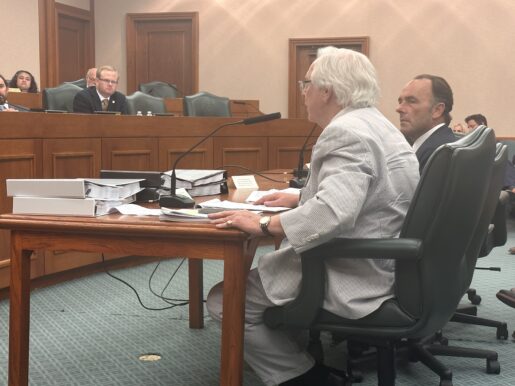

Photo: Bass and his attorney Ed McCarthy testifying before the House Natural Resources Committee

A longtime capital staff member sought DX out at the hearing to comment, “This was all set up to drag Mr. Bass through the mud for political reasons. They want to make an example of him for personal political gain because he’s wealthy, successful, and makes a convenient target.”

Another attendee commented, “This is all fearmongering for political reasons, which is the biggest obstacle to innovative solutions to actually solve the crisis, like what Mr. Bass is proposing.”

Power, Politics & Property Rights

When asked about the suggestion of a personal political motive behind the hearing, Harris told DX, “That suggestion is just absurd on its face and doesn’t dignify a response.”

Bass also said that Harris has never reached out to him, his attorney, or other representatives from CEM to meet privately to discuss his project and the supporting data.

Harris replied, “I really can’t imagine a more tone-deaf response from Mr. Bass. He buys property under the guise of wildlife conversation and environmental management, then is surprised when the entirety of the population of those counties rises in strong opposition to him stealing billions of gallons of water out from under us, then thinks it’s a political set up when I call a hearing while he’s doing all this in the county of the chair of the committee with jurisdiction over water?”

Harris continued, “A political setup would have been to have the hearing without inviting him to testify.”

The hearing lasted 10.5 hours in total, finishing just around midnight.

Bass summarized his message to the committee: he’s following the law, filling a gap in state water demand/infrastructure, and putting private capital to work where the government hasn’t been able to solve a real need without burdening Texas taxpayers.

Despite Bass’ testimony, Harris and other elected officials continue to promote a narrative to their constituents that Bass is “stealing” Anderson County’s water — a claim that “the hearing proved doesn’t hold up legally or factually,” said McCarthy.

Harris acknowledged that, from his point of view, the “Rule of Capture” that Bass is legally operating under needs to be updated, at least from the point of view of high-capacity wells. “It was wind-driven windmills in 1904”, Harris said. “They couldn’t contemplate high-capacity wells then. The amount of damage being done is not the original intent.”

The problem for concerned legislators is that Bass isn’t “stealing” anything – at least not by current law.

He owns the land.

He’s using private money.

He’s operating under the same legal framework that’s been in place for more than a century.

As Bass’ testimony went on deep into the night, it was acknowledged by most legislators in attendance that Bass was breaking no laws. Some lawmakers stepped out of the hearing room following the end of the hearing to take photos with him and thank Bass for attending and bringing “forward-thinking solutions” for them to consider.

Bass has since met with other state legislators from the regions of the state interested in need of water who are interested in CEM’s plan to transport water to their districts.

A Texas-sized Opportunity or Opportunity for Profiteering From a Critical Natural Resource?

Bass further told DX that his plan is like what was seen during the natural gas boom. Landowners leased or sold their mineral rights and shared in the upside.

The same private property rights that apply to oil and gas apply to water. Texans are allowed to responsibly monetize what’s under their own land — especially when the state hasn’t taken any action to solve the water crisis.

“It’s one step, but a step we need to take before it’s too late,” Bass said.

When Bass asked the legislators if any of them had fully read the 2022 Water Plan, HD 9 Rep. Trent Ashby acknowledged he had not read the complete document. Ashby indicated that Bass was likely following the law, but he would oppose the project anyway. DX reached out to Ashby to ask him on what basis of law he opposed the project, but did not receive a response.

“We acquired Redtown Ranch in July of 2022,” Bass told DX. “We then invited local leaders (including Anderson County Judge Carey McKinney, superintendents, and others) to walk the land with us. We explained our vision: regenerative ranching with Red Angus cattle, selective pine thinning to restore sunlight and succulents, and thoughtful hydrological studies to explore water project potential. The response was overwhelmingly positive. They saw that we were proper stewards—not speculators.”

Since Bass appears to be following the law in his request for new test well permits, the next step in the process is for CEM to attend a meeting of the State Office Administrative Hearings (SOAH), which will try to resolve the conflict between the law and the complicated supporting data.

That hearing has yet to be scheduled. In the meantime, Texas keeps searching for solutions to its water crisis.

Editor’s note: Dallas Express’ Publisher owns property in Henderson County in Representative Harris’ district. DX’s Chief Executive Officer attended college in overlapping years with Mr. Bass at Texas Christian University.